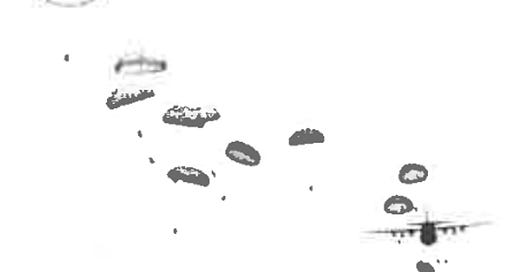

Packed with paratroops, the hulking C-130 Hercules turboprop ploughed onward through the clouds blanketing South Vietnam’s central highlands.

It was October 5, 1967 – monsoon season – and thick cloud cover obscured the target up ahead: an abandoned A-camp that, as they worked to counter North Vietnamese and Viet Cong infiltration from Cambodia, Special Forces commanders had decided to reopen. Nestled among grass-covered hills less than five miles from the border, the camp presented challenges to the aircrews and the paratroops: The drop zone was small and surrounded by woodland, while its proximity to the border meant a small mistake could send paratroops into neutral Cambodia.

The 49 troops readying themselves to jump were the pathfinders whose job it would be to secure the drop zone for the main body of paratroops. The pathfinder element was divided between 37 Montagnards and about a dozen Green Berets, led by Maj. Chumley Waldrop, the SF company executive officer. Sitting close to him was the man whose job it was to examine the camp’s small airstrip to see if it could still handle fixed-wing aircraft. That man was Willie Merkerson.

The main body consisted of 50 Green Berets and 275 LLDB and Montagnard troops, according to author Shelby L. Stanton’s book “Green Berets at War.” They were aboard four C-130s about half an hour behind the pathfinders.

Many of the Green Berets were excited for the mission. All Green Berets were airborne qualified, and most yearned to make a combat jump, which would give them the right to adorn the parachutist badge on their uniforms with a small bronze star (or “mustard stain,” as it’s often called). Combat jumps were not unheard of in Vietnam but were nonetheless quite rare.

“I had been in the airborne for five years and made over eighty jumps with no likelihood that I’d ever get to make a combat jump,” writes Jim Morris, one of the Green Berets on the mission, in his acclaimed memoir, “War Story.” “I wouldn’t have missed that opportunity for ten thousand dollars.”

Merkerson’s enthusiasm was somewhat more restrained. “I was happy that I was selected to go,” he said. “But I wasn’t excited – Oh Lord, let me get that thing, I need that thing, I need the star [on my wings]. Oh no, that wasn’t me.”

The Green Berets had arranged for chilled champagne to be on hand at the drop zone if the mission went well. But that was a big “if.” No one on the planes had any idea whether enemy forces would be lying in wait for them when they landed.

Despite flying only 600 feet above ground level, the pathfinders’ C-130 couldn’t get underneath the clouds. It would have to be what airborne soldiers call a blind drop. “Normally you don’t jump like that,” Merkerson recalled.

Waldrop was undeterred. “You’re going out of this damn plane one way or another,” he said, according to Merkerson.

As the plane reached the drop zone, the lights beside the jump doors on each side of the aircraft turned from red to green. Using both arms, Waldrop, a jumpmaster for the flight, pointed down and to the sides, the signal for the first jumpers to stand in the doorways. Seconds later, one by one, they stepped into the gray unknown.