Zeroed Out: How JSOC’s Omega teams enabled the CIA’s Afghan militias

The joint CIA/JSOC hunter-killer teams stalked Afghanistan for nearly twenty years

Thin clouds veiled the quarter moon that hung in the Afghan night sky as several dozen Toyota Hilux pickup trucks slowly ground to a halt.

Doors opened and scores of armed men, members of an Afghan militia, jumped out before the drivers began turning the vehicles around in case a quick extraction became necessary. Their target was straight ahead, a cluster of compounds in Panjwai district, a hotbed of Taliban support about 18 miles southwest of Kandahar. It was the summer of 2007 and, according to intelligence developed by the CIA, the Taliban had recently taken over the little village, kicking the civilians out of their homes and turning the place into an armed camp.

Mixed into the group of about 150 Afghan militiamen were a dozen or so Americans, and at least two Canadian special operators.

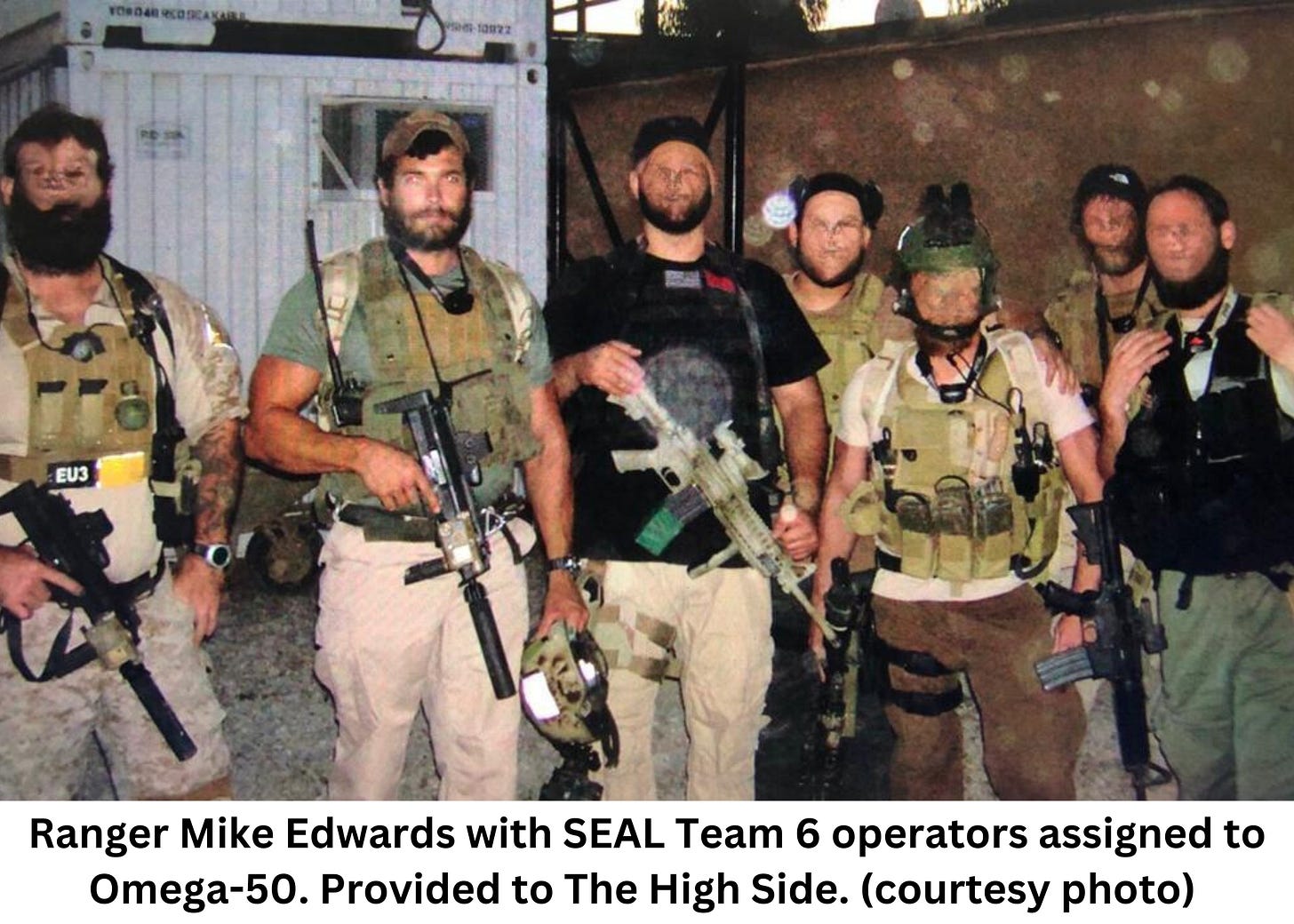

“I’ll go on and scout up ahead,” Staff Sgt. Mike Edwards, an Army Ranger, told a pair of snipers from Canada’s most elite special operations unit, JTF-2, who were tagging along for the mission. (The Canadian operators lived on the same base as the Americans, who found them useful to bring along on missions as, in addition to their military skills, both spoke Pashto.)

Sick with food poisoning, Edwards had been on the verge of staying back at the base until his team leader, a SEAL Team 6 chief petty officer, told him he really needed him on this mission. Now it was 2 a.m. and as he crept toward the enemy stronghold, Edwards felt as if a switch flipped inside him, the familiar rush of adrenaline jolting his senses alert. He was ready for combat.

Edwards was part of a secret military effort in Afghanistan called the Omega program that provided small teams of special operators to support the CIA’s use of locally recruited militias as proxy forces to go after insurgent leaders. In turn, the CIA personnel and their militias would sometimes support special operations missions.

Dating to the earliest years of the Afghanistan war, and widely viewed as a success inside the special operations and CIA communities, the Omega teams took part in the hunt for kidnapped U.S. soldier Bowe Bergdahl, helped capture numerous individuals who became prisoners at Guantanamo Bay, and played a key role in tracking and killing American al-Qaida propagandist Adam Gadahn.

“The Omega contingent provided incredible capability to the overall effort” with the CIA’s militias, said a former senior Defense Department official. “It made a really good program into a great one.”

But other observers have heavily criticized the program, in part due to numerous war crimes allegations aimed at the militias. Still others said the Omega teams, like other special operations programs that focused on night raids with carefully vetted Afghan partner units, had limited operational and strategic impact. “They did more harm than good,” said an academic who worked closely with coalition forces in the field in Afghanistan, and who asked to remain anonymous because he still works with special operations forces.

In addition, several Omega teams experienced frictions between the military personnel and their CIA colleagues, according to team veterans. Nonetheless, the Omega program appears to have provided a template for many of the United States’ subsequent attempts in other countries to use proxy militias as a tool of U.S. foreign policy.